It’s become fashionable among American pundits to question the value of post-secondary education; and nowhere are these opinions more sharply aimed than at the arts and humanities.

It’s become fashionable among American pundits to question the value of post-secondary education; and nowhere are these opinions more sharply aimed than at the arts and humanities.

At an alarming rate, young people are told to get trained for utilitarian jobs, and to forego liberal education in favor of technical schooling. Conversely, it’s occasionally posed that the MFA has become the new MBA, and that creativity and the ability to solve complex problems in non-linear ways, is prized by CEOs.

Indeed, in a previous professional incarnation, as an associate dean at an Ivy League university, I’d routinely hear CEOs implore us to send history, philosophy, and English concentrators to them precisely because humanities students learn to think critically and solve problems in useful ways. At the heart of all these matters, and my skepticism about them, is the way these arguments see knowledge and people as instruments for the perpetuation of certain facets of economy—and implore students to prepare for servile lives within institutions that are failing the majority of the world’s population.

The stridency and contradictions amongst these arguments is confusing, and the resulting muddle creates anxiety for students and teachers alike. Working with graduate students in the arts, I’m regularly engaged in conversations about the economic viability of an MFA degree, and asked by students to help them situate their work within commercial markets. Sometimes the market is perceived as encompassing traditional arts venues—galleries, museums, publishing, theaters, or the contemporary system of patronage: grants, fellowships, and residencies. Other times the market is seen as the academy itself—and its ever-more-competitive field of faculty jobs.

While I don’t mean to discount or diminish anyone’s very real concerns about livelihood (I feel them acutely, too), increasingly it seems our culture is missing the point of education. And, perhaps more specifically in relation to the arts, an undue obsession about art’s economic acceptance threatens to dull its real possibility.

It’s important to remember that these tensions aren’t new and that artists didn’t (and don’t) always look to colleges for their education. Ben Shahn, giving the Norton Lectures at Harvard in 1956, as the MFA degree was taking shape, considered the relationship of the arts and the academy with some ambivalence:

It’s important to remember that these tensions aren’t new and that artists didn’t (and don’t) always look to colleges for their education. Ben Shahn, giving the Norton Lectures at Harvard in 1956, as the MFA degree was taking shape, considered the relationship of the arts and the academy with some ambivalence:

“…there is always the possibility that art may be utterly stifled with the university atmosphere, that the creative impulse may be wholly obliterated by the pre-eminence of criticism and scholarship. Nor is there perfect unanimity on the part of the university itself as to whether the presence of artists will be salutary with its community, or whether indeed art itself is a good solid intellectual pursuit and therefore a proper university study” (The Shape of Content, p. 2).

And writing in the 1990s, Adrienne Rich considers these matters in relation to art’s power to subvert and transform established cultural patterns:

“I was looking for poetics and practices that could resist degraded media and a mass entertainment culture, both of them more pervasive and powerful than earlier in the century… There was nothing new about this; artists have long made art against the commodity culture. And innovative or transgressive art has itself been commodified, yet has dialectically frictioned new forms and imaginings into existence” (Arts of the Possible, p. 7).

Even earlier, in his meditation on art within Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, and in relation to how one might name the very book he’s writing, James Agee takes up Rich’s dialectical frictioning, as he struggles to weigh creative integrity against cultural enshrinement:

“Above all else: in God’s name don’t think of it as Art.

“Every fury on earth has been absorbed in time, as art, or as religion, or as authority in one form or another. The deadliest blow the enemy of the human soul can strike is to do fury honor. Swift, Blake, Beethoven, Christ, Joyce, Kafka, name me a one who has not been thus castrated. Official acceptance is the one unmistakable symptom that salvation is beaten again, and is the one surest sign of fatal misunderstanding, and is the kiss of Judas” (Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, p. 15).

I offer these twentieth century examples not to suggest that they’re the only way to see these matters. Rather, because each reveals the struggle artists face in resisting and critiquing institutional power while, perhaps obliquely or unconsciously, sometimes intentionally, embracing it.

I offer these twentieth century examples not to suggest that they’re the only way to see these matters. Rather, because each reveals the struggle artists face in resisting and critiquing institutional power while, perhaps obliquely or unconsciously, sometimes intentionally, embracing it.

It also feels particularly telling that these matters remain so relevant and unresolved today. Among these examples, it’s only Adrienne Rich who offers us a progressive way forward, and a clue as to how the arts remain a vital force in culture creation. And she does it by establishing a category of the arts both beyond and enmeshed within commodity culture—suggesting that artistic transgression is its own kind of Trojan horse. But more than this, she suggests how the arts offer us hope for a culture that might yet escape the peril of recycled experience, and economic goals that lack humanist values or aspirational vision. And while Rich was no facile advocate for MFA programs or the enshrinement of artists within ivory towers, she might yet offer MFA programs a way forward, too.

Making culture is never easy or without risk, and unfortunately the lives of artists may always carry the extra burden of balancing concerns about livelihood with vocation. As James Baldwin said about writing in an interview in the Paris Review, “It’s a terrible way to make a living. I find writing gets harder as time goes on. I’m speaking of the working process, which demands a certain amount of energy and courage (though I dislike using the word), and a certain amount of recklessness.”

Baldwin’s position, of course, supposes that the work of a writer is to advance the culture, and to push against established boundaries.

Like the CEOs I met earlier in my career, I understand how powerfully arts’ methods can be used to solve problems in various spheres of human concern. While creativity certainly may be employed within the service of institutions, such creativity is always bounded, and as Agee points out, is likely to be absorbed into existing authority. And as much as I value the professorate and higher education’s purpose, I don’t teach in Goddard’s MFA in Interdisciplinary Arts (MFAIA) program to only prepare the next generation of arts faculty. I’m far more interested in helping the students with whom I work consider how they might fully navigate the world as artists—manifesting their fury, dialectically frictioning new forms and imaginings into existence, and building new spaces for human possibility.

Yes, this may involve teaching and it may include participation in the commercial art worlds (after all we live within the world’s existing institutions, and Rich may be right about the possibility of art’s subversion), but hopefully will always work to situate artists in spaces and places that we’ve yet to imagine. Because it’s only in spaces such as these that we can hope to break the hold of injustice, break free of the idea that our purpose is to serve an economy that doesn’t sufficiently serve us, and consider how both liberal education and the arts, perhaps in a dance that’s yet to be adequately choreographed, can work together to advance human freedom. And it’s inquiry related to these questions, rather than simple answers about employment—no matter the how deeply we feel urgency in a search for those answers, too—that I believe can animate every MFAIA education.

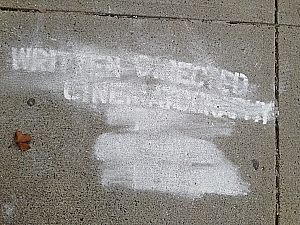

Photographs by the author, c. 2014.